Safety: Botanical Identification and Toxicity

The Zero-Tolerance Discipline

In the preceding article, The Ethics of the Harvest, we explored the spiritual and reciprocal mandates of harvesting. But those mandates rest upon a cold, biological foundation: if you cannot identify the plant with 100% scientific certainty, you have no ethical right to harvest it.

On the Great Plains, the “backyard” is home to some of the most lethally toxic plants in North America. To the untrained eye, the roots of the Water Hemlock look like wild parsnips; the leaves of the Death Camas look like edible onions; and the berries of the White Baneberry look like harmless fruits. In this 2,200-word deep dive, we explore the science of botanical identification, the primary toxic species of the High Plains, and the rigorous protocol of the “Zero-Percentage” Rule.

1. The Anatomy of Oversight: Why We Fail to See

Modern humans have evolved a specific type of sensory filter known as Plant Blindness. Because plants do not move in the high-speed manner of predators or prey, our brains tend to process them as “wallpaper”—a monolithic background of green.

To be a safe ethnobotanist, you must dismantle this filter. You must move from “seeing a plant” to “observing a botanical structure.”

The Five-Senses Audit

Safe identification requires a sequential audit of properties:

- Phyllotaxy (Leaf Arrangement): Are the leaves opposite, alternate, or whorled? This single observation can eliminate 50% of potential look-alikes.

- Margin and Veining: Are the leaf edges smooth (entire), serrated (saw-toothed), or lobed? Do the veins reach the edge of the tooth or the center of the notch? (In Water Hemlock, the veins uniquely reach the notches).

- Stem Architecture: Is the stem hollow? Square? Hairy? Spotted?

- Inflorescence (Flower Structure): The number of petals, the shape of the sepals, and the arrangement of the flower head (umbel, spike, raceme).

- Olfactory Triggers: Does the crushed leaf smell like citrus, mint, or rank, “mousy” chemicals?

2. Tools of the Trade: Bridging New and Old

Accuracy is rarely a product of memory; it is a product of Verification.

The Magnifying Glass or Loupe

Many of the key diagnostic features of a plant—such as the presence of glandular hairs (trichomes) or the specific shape of a seed pod—are too small for the naked eye. A 10x jeweler’s loupe is the most important survival tool in your kit. It forces you to slow down and look at the “fingerprints” of the plant.

The Dichotomous Key

This is the “logic tree” of botany. A field guide that uses a dichotomous key asks you a series of binary questions (e.g., “1a: Stem is square — go to 2; 1b: Stem is round — go to 3”). This methodology removes “guessing” from the process. If you follow the key accurately, you are led to the only possible species name.

3. Profiles in Toxicity: The Lethal Look-Alikes

The Great Plains host several “double-agents”—toxic plants that mimic the appearance of common edibles or medicines.

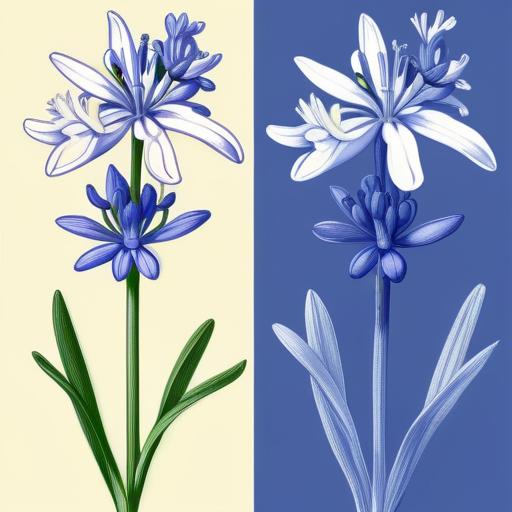

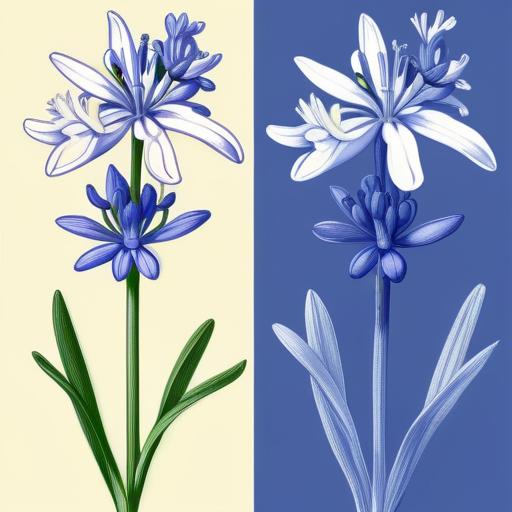

I. Death Camas (Zigadenus venenosus) vs. Blue Camas (Camassia)

This is the most famous and dangerous look-alike in the West.

- The Edible: Blue Camas was a staple carbohydrate for many tribes. Its bulb is sweet and nutritious when roasted.

- The Killer: Death Camas contains zygacine, an alkaloid that causes rapid heart failure and respiratory paralysis.

- The Danger: When not in bloom, the grass-like leaves of both plants are virtually identical.

- The Protocol: Traditional harvesters often marked their Camas patches while they were in bloom (Blue flowers vs. White Death Camas flowers) and only returned to dig them in the fall when the bulbs were at their peak. Never harvest a “mystery” bulb.

II. Water Hemlock (Cicuta maculata) vs. Wild Carrot/Parsnip

Water Hemlock is arguably the most violently toxic plant in North America. A piece of the root the size of a marble contains enough cicutoxin to kill an adult.

- The Identification Key: Observe the stem base. Water Hemlock has a thick, partitioned rootstock with air chambers that resemble a “wasp’s nest” when sliced open. Furthermore, its leaves have veins that end in the notches of the serrated edge, whereas almost all other look-alikes have veins that end at the points of the teeth.

III. Monkshood (Aconitum) vs. Geranium

- The Killer: Monkshood contains aconitine, a toxin that can be absorbed through the skin, causing numbness and eventually death.

- The Danger: Before flowering, the deeply lobed leaves of Monkshood can be mistaken for Wild Geranium or larkspur.

- The Protocol: Always wear gloves when handling unknown members of the Ranunculaceae (Buttercup) family.

4. The Chemistry of Poison: Alkaloids vs. Glycosides

Ethnobotanical safety requires a basic understanding of how plants kill.

- Alkaloids: Nitrogen-based compounds (like nicotine, morphine, and zygacine). They tend to target the nervous system, mimicking or blocking neurotransmitters.

- Cardiac Glycosides: (Found in Indian Hemp and Milkweed). These target the heart’s electrical system, causing irregular rhythmic patterns and potential arrest.

- Phototoxins: (Found in Giant Hogweed). These do not kill on contact, but they make your skin hyper-sensitive to UV light, leading to third-degree burns when exposed to the sun.

5. The “Rule of One”: Starting the Relationship

Even when a plant is correctly identified as edible or medicinal, the ethical and safe practitioner follows the Individual Tolerance Test.

- Individual Variation: Every human body reacts differently. A plant that is a medicine for a thousand people might be an allergen for one.

- The Protocol: When trying a new plant for the first time:

- Perform a “skin test” (rub the plant on your inner wrist).

- Perform a “lip test” (touch a small amount to your lips).

- If no reaction occurs after an hour, ingest a very small (“pea-sized”) amount and wait 24 hours.

Note: This protocol is only for plants you have already identified as 100% safe. It is NOT a way to test if a mystery plant is toxic.

6. Indigenous Safety Systems: Taboo as Technology

Indigenous nations did not have laboratories, but they had Observation and Taboo.

- Teaching through Story: Many “scary stories” or legends about specific animals or locations were actually mnemonic devices to warn children away from toxic plant patches.

- The Reference Specimen: Families often kept “pressed” or dried versions of both the medicine and its toxic look-alike to show the younger generation the difference in the bark or seed structure.

7. The Seasonal Shift in Toxicity

A plant’s toxicity is not a static property. It varies based on the plant’s lifecycle and environmental stress.

- Concentration: Some plants are only toxic in their early “shoot” stage, while others (like the Elderberry) have toxic stems and leaves but edible fruits.

- Stress Response: Plants often produce more toxins during a drought as a defensive measure. A plant that was “food” in a wet year might be “toxic” in a dry one.

8. Conclusion: The Burden of Knowledge

Being an ethnobotanist is an act of high-stakes responsibility. You are not just a harvester; you are a guardian of the knowledge that keeps your community safe.

If you provide a tea of “Wild Mint” to a friend that turns out to be Hemlock-Parsley, you have committed an act of gross negligence. The “spirit of the plant” requires us to be as rigorous in our science as we are in our respect. The field guide, the loupe, and the herbarium specimen are the holy texts of botanical safety.

Respect the plants. Learn their faces. And if you are in doubt, let it stand. The prairie will wait for you to study more.

Technical Summary: High Plains Priority Toxins

| Toxic Species | Look-Alike | Primary Toxin | Symptom |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water Hemlock | Wild Parsnip | Cicutoxin | Seizures, death within hours |

| Death Camas | Blue Camas / Wild Onion | Zygacine | Heart failure, paralysis |

| Poison Hemlock | Queen Anne’s Lace | Coniine | Respiratory failure (ascending) |

| Monkshood | Wild Geranium | Aconitine | Numbness, cardiac arrest |

| Snow-on-the-Mountain | Wild Sage (mistaken) | Diterpenes | Severe skin blistering |

Recommended Safety Gear

- 10x Triplet Jeweler’s Loupe: The standard for field identification.

- Peterson Field Guide to Edible Wild Plants (Eastern/Central): The gold standard for North American ethnobotany.

- Nitrile Gloves: Essential for handling any member of the Parsley or Buttercup families until ID is confirmed.

View Botanical Safety and Identification Equipment on Amazon

Next in our Ethics Series: Respect - Indigenous Data Sovereignty and Traditional Knowledge.